Our students’ ability to read is essential to their success. Regardless of the grade or subject we teach, reading is one of the most important skills we can foster in our classrooms. But despite its importance, many teacher preparation programs, especially those for middle and high school teachers, lack training in the science of how students learn to read. For this reason, when older student struggles with these skills, we often find it difficult to identify their specific needs or provide the right support. In the end, weak readers tend to fall further and further behind. Fortunately, there is a renewed interest across the country to ensure that teachers understand the Science of Reading, so students’ needs across every grade level can be understood and fully supported. Whether you are an experienced reading teacher or a high school math teacher looking for ways to support students struggling with advanced texts, this overview may be a helpful reminder of how we learn to master reading.

How Do Students Learn to Read?

For decades, people have debated how children learn to read. Some believe that reading is a natural process, like learning to speak. This theory encourages teachers and parents to surround children with good books as a way for students to develop their skills. While many children can develop reading skills in this way, there are a significant number of children who cannot. This is because research shows us that learning to read is not as natural as learning to speak. Written language is, in essence, a code – with certain combinations of letters predictably representing certain sounds. When we learn to read, we learn to crack this code. The most reliable way to ensure the greatest number of children learn how to read words is to teach phonics. With direct phonics instruction, kids learn the relationship between sound of the spoken language and the written word or letter (the “th,” “sh,” or “ea” letter combinations, for example).

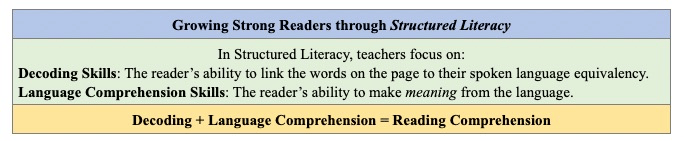

Of course, there is more to reading than seeing a word on a page and pronouncing it out loud. As such, there is more to teaching reading than just teaching phonics. Many schools now encourage a holistic approach to reading known as Structured Literacy that focuses on both decoding (i.e., phonics) and meaning (i.e., comprehension). While decoding may be important in the early years, comprehension skills continue to build from year to year through more complex reading selections.

Education Week recently published its “Science of Reading Spotlight” to emphasize the latest research and findings on Structured Literacy Instruction across the United States. Here are some important takeaways:

- Reading is much more than decoding words on the page: Students need to be able to recognize most words automatically and read fluently, attending to grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure. Students also need build comprehension and vocabulary. But knowing how to decode is an essential step in becoming a reader. If children can’t decipher the precise words on the page, they cannot become fluent readers.

- Not all phonics instruction is created equal. The most effective phonics programs are those that are systematic. A systematic program teaches students all of the letter-sound combinations, in a specific sequence (not just the ones students struggle with). Teaching is explicit, with teachers telling students which sounds correspond to what letter patterns, rather than asking students to figure it out on their own or make guesses.

- While many reading programs teach students to identify a word by guessing with the help of context cues, these “cueing strategies” are not supported by research. In fact, research suggests cueing instruction can make it more difficult for children to develop phonics skills because it takes their attention away from the letter sounds. It’s also interesting to note that cueing strategies are based on the most common errors of new or struggling readers, rather than the successful practices of proficient readers! (Most skilled readers actually sound out new words to decode them, rather than guess).

- Reading to young children is still one of the most valuable ways parents can support early readers. Even though many children don’t learn to read naturally from being exposed to reading, the quality of their spoken language and vocabulary does impact their reading ability. Children who have been read to regularly tend to use and understand more words, longer phrases, and more sophisticated sentence structures. Reading with trusted adults also helps children develop a love of reading.

- There are five essential components of reading: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Teachers of every grade level can support reading development with these activities: Having students read out loud with guidance and feedback improves fluency. Vocabulary instruction, both explicit and implicit, leads to better comprehension—and it was most effective when students had multiple opportunities to see and use new words in context. Teaching comprehension strategies (like predicting, visualizing, using story maps, etc.) can also lead to gains in reading achievement.

Regardless of the age we teach, we can help students build fluency and comprehension by providing a rich variety of engaging texts to read in our classrooms. We can directly teach students the academic vocabulary relevant to our subject and encourage regular notetaking to help students develop tackle increasingly complex texts. And if we see students struggling to complete daily reading work in our classes, we can look to the science of reading to where we might help our students grow.